Cars jammed the Chester Shell Elementary School parking lot and spilled along side streets and into an empty field. Inside the cafeteria, it was standing room only, and latecomers leaned against the walls.

Many attendees sported t-shirts: purple ones that said “I support Plum Creek” or green ones that said “Stand by Our Plan.”

When Alachua County Commissioner Mike Byerly stood up to speak, he said, “I sort of feel like I’m at a football game – I…see two colors of jerseys.”

Community leaders and concerned Alachua County residents met June 23 to discuss updates to the proposed Plum Creek development plan that would consolidate conservation areas and allow major employers to take root in the eastern part of the county.

Although the plan has already been three years in the making, the Monday night town hall meeting made one thing clear: the outcry on either side is not going to die down anytime soon. Residents asked questions and talked over each other during a public comment segment, and organizers presented differing visions for how to help the county grow.

Plum Creek is Alachua County’s largest private landowner, holding 65,000 acres. The county asked the national land management and conservation company three years ago what its intentions were for the land and so began the talks.

As the first presenter of the evening, Missy Daniels with Envision Alachua gave an update on the project’s timeline.

She said that on the following day, Plum Creek would submit the final responses to county staff questions, which would signal that the Envision Alachua Sector Plan is ready for official review.

Because the plan calls for an area of major development near Hawthorne which would extend beyond Alachua County, she said the group will need to coordinate with Marion County and the cities of Gainesville and Hawthorne to move forward.

On July 8, Plum Creek will present the sector plan to the Alachua County Commission. Then, she said, it will set up public hearings which could be divided topically and could include general overview, environmental issues, transportation, economic fiscal impact and the east Gainesville plan.

Next, Justin Williams, a manager of Cracker Boys Hunt Club, spoke in support of the Plum Creek initiative.

He said he was initially skeptical three years ago when he entered talks with Plum Creek because he wanted to ensure hunting was included in the land conservation requirements. As the plan took shape, he said, he was impressed that what community members asked for was taken into consideration and included. He got the protections he requested for his club.

Now, Williams said he is a strong proponent of the Plum Creek plan rather than the counter-plan presented by the county because there “wasn’t much in it for this side of the county.”

He said Hawthorne is a community “slowly unraveling at the seams” after the closing of the Georgia Pacific plant, and bringing industry back to east Alachua County would enable families to better carve out a livelihood there.

“The plan to me was about preserving quality of life – providing opportunity for the next generation,” he said. “This is not going to happen in my generation – but maybe [for] my children.”

Rose Fagler, a Plum Creek spokeswoman, said jobs are needed for all residents, including those in the more rural, less wealthy east side of the county. But under the county’s current model, she said, many of the entry-level jobs go to the county’s roughly 75,000 students.

“That’s why you have what we have in our community: a lot of working poor,” she said.

But Commissioner Mike Byerly disagreed and said the county’s existing comprehensive plan presents a better solution.

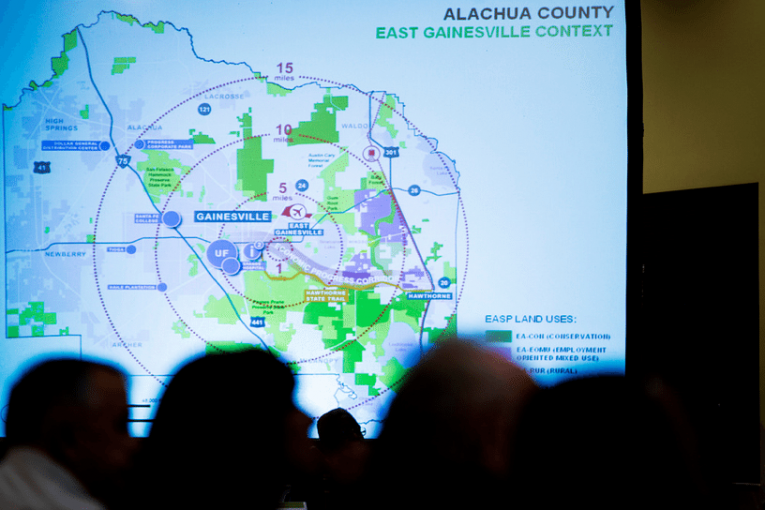

To explain, he pointed to a map of Alachua County and gave the audience a geology lesson. He said the east side is mostly clay – which creates standing water – and the west side of the county is sand – which promotes drainage.

“To make this area suitable for that kind of growth,” he said, pointing first to the east side and then to the west side, “you’re going to have to do a lot of old-school Florida dredging and draining.”

The county plan is more feasible, he said, and it doesn’t require modifying existing environmental standards. It asks Plum Creek to adhere to the same environmental standards everyone is subject to, including all the developers.

In addition, he said, the Plum Creek plan doesn’t generate more development than the county is already facilitating. The place the development occurs is the difference, he said.

“They won’t be doing anything that isn’t already happening in Alachua County,” he said. “It’s just a question of where.”